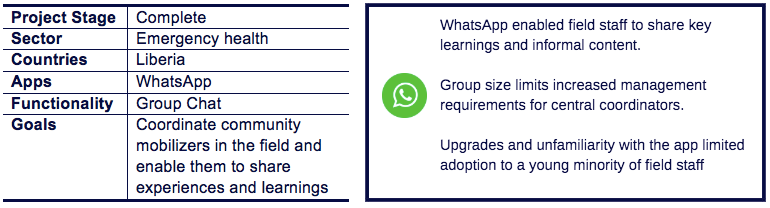

In response to the Ebola outbreak in Liberia, in 2014 Mercy Corps developed the Ebola Community Action Platform (ECAP), a program to help communities learn how to protect themselves from Ebola and to access care. Eight hundred community mobilizers from 79 partner organizations were given phones, content and training to disseminate and collect community-level information about Ebola knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP).

The primary use of the smartphones was for mobilizers to report on their activities in communities via a separate data collection app. Mercy Corps staff believed the phones could also be a useful tool for the mobilizers to support one another by sharing learnings, experiences and tips, which could improve their effectiveness. Mercy Corps had good experiences using WhatsApp, even in areas of poor connectivity, so they installed WhatsApp on all the mobilizers’ phones. While there was no published API, B-WhatsApp was identified as a service for bulk messaging so that the app could also back up ECAP’s SMS system for coordination and alerts.

KAP data collection via Open Data Kit (ODK) was a critical project deliverable, while the use of WhatsApp was viewed as an experiment. The mobilizer training reflected this, allotting just one hour of training for WhatsApp. Training focused on basic app functionality and adding mobilizers to chat groups. Mobilizers were simply instructed to discuss and share experiences in the field. Mercy Corps staff also participated in the chat groups, but only as silent observers. This passive and unstructured approach generated low participation. To increase engagement, Mercy Corps began curating evening discussions, proposing topics, and encouraging mobilizers to share stories and suggestions based on experiences in their communities.

ECAP personnel differ in their assessments of WhatsApp. All agree that trainers and mobilizers had little familiarity with the app and low technical literacy, and that the emergency context resulted in insufficient

training. These issues were exacerbated by technical problems during the short training period. WhatsApp was not available on Google in Liberia at the time, forcing users to download APK files from a web link to

install and upgrade the app. In the end, WhatsApp was installed on only 85 percent of the phones, many suffered long periods of failure, and usage was concentrated among the youngest 25 percent of mobilizers. Content

shared was often informal, including selfies and photos from journeys to remote communities. The ECAP Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) Lead saw this as distracting, while the Digital Lead saw it as motivating and

providing valuable storytelling material. Both agreed that when WhatsApp discussions were stimulated by a Mercy Corps admin, they produced critical learnings. However, these benefits required significant M&E staff

time in the evenings and distracted from primary responsibilities. WhatsApp’s 100-member group limit made the task more difficult, requiring five parallel group conversations at a time.

As Ebola came under control, Mercy Corps’ use of WhatsApp in Liberia ended in 2015, and the Digital Lead left the project. A second phase, ECAP 2, launched in 2016 to mobilize community preparedness but

turned to SMS and voice calls to communicate with communities. For staff learning and coordination, ECAP 2 started a Facebook page and began using Facebook Messenger. Reflecting on ECAP 1, the M&E Lead believes

Facebook Messenger would have been superior due to relatively greater penetration and familiarity in Liberia and the impact of Free Basics. The Digital Lead believes it would have encountered the same issues and

achieved the same results as WhatsApp.