Since 2013, the mobile Vulnerability Analysis and Mapping (mVAM) project has monitored food security trends through short surveys of World Food Programme (WFP) beneficiaries (i.e., food insecure people around the world) using SMS, live phone interviews, online surveys and an interactive voice response (IVR) system. mVAM then anonymizes, cleans and analyzes the data, sharing the results as a public good and using them internally for humanitarian decision making. mVAM also shares information with beneficiaries through IVR and Free Basics (free websites), which beneficiaries can call and browse for free to access information about food prices and WFP assistance (e.g., food distribution dates) or provide feedback using the same channels. Since its inception, mVAM has worked in 34 countries, primarily in sub-Saharan Africa.

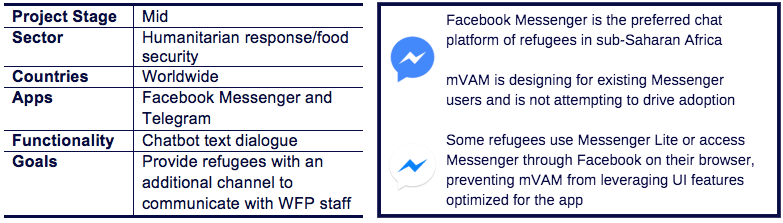

In 2016, mVAM decided to experiment with chatbots as a new channel for beneficiaries to report and access WFP information, recognizing the growing popularity of messaging app in beneficiary countries, particularly among young people. mVAM engaged InSTEDD to prototype “The Food Bot” on Telegram and showcase the idea to donors and partners. However, early user testing in Haiti, Nigeria, and Kenya found that beneficiaries were unfamiliar with Telegram. Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp were the most commonly used messaging apps. In 2017, the team subsequently received funding to develop The Food Bot on Facebook Messenger. They conducted two rounds of user testing in the Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya and in Maiduguri, Nigeria, with refugees, internally displaced people, and with WF Country Offices. Field testing found that while not all refugees use Facebook Messenger, it was popular amongst 20- to 40-year-olds and community leaders, and there was significant demand for a chatbot service amongst country teams.

Initial testing with beneficiaries suggested that The Food Bot would be useful for refugees in Kenya to provide feedback and submit complaints about WFP services, while In Nigeria it could be used to collect price information from traders. However, after testing with WFP Country Offices, mVAM and InSTEDD concluded that a single generic Food Bot would be insufficient to meet their diverse needs. Instead, mVAM concluded that WFP Country Offices and other humanitarian teams needed a web platform to quickly build and deploy their own custom chatbots with little in-house programming skills. mVAM and InSTEDD pivoted and began developing a chatbot builder platform for the humanitarian sector called AIDA. mVAM will become AIDA’s first major user in late 2018, as InSTEDD refines it for release as an open-source tool at the end of the year.

WFP and InSTEDD’s experience demonstrate the importance of conducting extensive user research and iterative testing before deploying messaging apps for development. In addition to their borader pivot from a single chatbot to a chatbot builder platform, testing also revealed insights about how different beneficiary groups access and use Facebook Messenger, and thus which user interface features they experience. While some download and use the Facebook Messenger app, others use Messenger Lite, which eliminates some advanced features to save space and use less data. To avoid data charges, others log into the Facebook social media platform through their mobile browser and then use Facebook Messenger through the website. For these users, key UI features enabled through the Facebook Messenger API, such as multiple choice bubbles, are not supported. For AIDA, WFP and InSTEDD are designing chatbot interfaces that cater to all user groups, and eventually to multiple messaging apps.