Founded in early 2017, Tarjimly is a chatbot that connects aid workers and refugees with human translators around the world. The founders, all Muslim-American technology professionals, were moved to help refugees after watching news of the Syrian civil war and resulting refugee crisis unfold. When they volunteered in refugee camps, they spent most of their time helping translate for refugees and the aid workers who served them. Afterwards, they determined to apply their technical and linguistic skills to create a chatbot to supplement the shortage of translators available to refugees and aid workers.

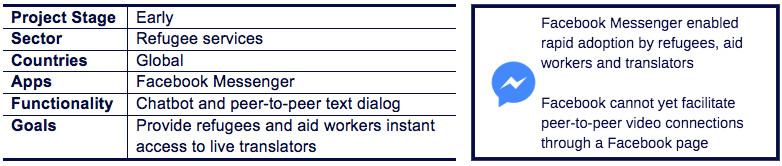

Despite a shortage of translators available to refugees and aid workers in person, the Tarjimly founders discovered a substantial supply of multilingual speakers willing to help remotely. What was required was a low-cost intermediary to connect translator supply with demand. The team believed that a chatbot linked to a popular messaging app would be the most practical solution in terms of development costs, overhead and onboarding. The team chose Facebook Messenger, calling the app the “the best and most robust” option to develop their chatbot and facilitate peer-to-peer conversations, and noting that aid workers, refugees and translators were already using Facebook to call on their global networks for assistance.

When first opening Tarjimly, users select whether they are a refugee, aid worker or translator. Translators then input which languages they speak and their available time slots. Thereafter, during the selected slots, Tarjimly asks the translators if they are available. Translators who confirm availability can then be matched with refugees or aid workers. When refugees and aid workers register, they select the languages they need to translate and wait as the chatbot searches for a translator according to language, availability and quality ratings. When the match is made, both parties receive an introductory message within the chatbot and a note that they are entering a live session. To protect the privacy of both parties, the chatbot does not connect users directly through their Facebook profiles but instead hosts a conversation within the chatbot dialog box. Both sides are able to exchange text, photos and audio notes to request or provide translations. Throughout, the refugee or aid worker can push a button to “end session,” prompting a translator rating that feeds back into the algorithm for future matching.

While Tarjimly originally expected that refugees would be using the app most frequently, in practice, most users are the aid workers who are helping refugees. Across all three user groups, onboarding has been smooth

due to Facebook’s popularity. In its first week, Tarjimly registered more than 1,000 translators and now hosts hundreds of sessions monthly. User reviews are mostly positive, and a common request from translators

has been for sustained relationships with refugees.

Tarjimly is now experimenting with a scheduling feature. While Tarjimly continues to believe Facebook Messenger is the best option to support its services, some limitations have frustrated expansion. Users

cannot connect via live video chat because conversations are hosted by the Tarjimly chatbot, which is connected to Tarjimly’s Facebook page, not a user profile. Facebook only facilitates video chat on Messenger

between two user profiles connected directly, not for conversations mediated by a chatbot. Tarjimly is also not language agnostic. It supports 11 languages and continues to add more. In the very long term, the Tarjimly

team envisions expanding its product to serve as a generic translation mediator between multiple different messaging platforms.